It’s easier to define what would ruin a good life than to define one.

It’s easier to explain failure modes than to communicate success.

It’s easier to know what we would refuse than what we would accept.

We know the walls before we know the room.

The obvious explanation is that we’re broken. Succumbing to a negativity bias or that evolution wired us wrong.

But that’s not quite it. The asymmetry isn’t in us, but the structure of reality itself.

So, why are the walls easier to find than the center?

Success and failure have different logical structures. They aren’t symmetric opposites, they’re different things.

Success is a conjunction. For example, finding love requires chemistry AND timing AND compatibility AND mutual availability AND shared values. Every variable must land in range at the same time.

Failure is a disjunction. Bad chemistry OR bad timing OR incompatibility. Any single thing outside its range is good enough to be met with failure.

If you think of it visually, success is the tiny sliver where all the circles overlap. Failure is a vast space where you only need to be outside one.

If five things must go right, each with 70% odds, the overall probability is 17%. The math is punishing, the conjunctions shrink, the disjunctions expand.

When something fails, you can usually find the cause. The single circle you stepped outside. This is why postmortems work. When something succeeds, you often can’t really reverse engineer it. Twelve things went right, and you can’t really isolate which actually mattered.

In other words, failure is visible and success is blurry.

The negative leaves clean data. The positive leaves mystery.

Once you see this logic, you can find it everywhere.

Take biology, the immune system can’t enumerate every possible threat. The space is infinite and mutating. So it models self instead. Anything that does not match gets flagged as foreign. Health is defined negatively. Health is the absence of not-self.1

Or in theology, Thomas Aquinas opens his writing on God with an interesting move. We cannot say what God is, only what God is not. Infinite, so not finite. Eternal, so not temporal. This is the via negativa. Aquinas is being precise. Some realities are too vast to approach directly.2

Even in fiction, Dystopias are vivid. 1984, Brave New World, The Handmaid’s Tale. Each details specific wrongs. Things like surveillance, thought control, coercion. Pretty concrete and describable. If you try to write a utopia with the same details you might find that you can’t. It comes out thin, unconvincing, vaguely sinister. Dystopia is a disjunction of wrongs. Utopia is a conjunction of goods that must match in ways nobody can quite articulate.

The pattern seems to hold across domains because it’s not about the domains, but about the geometry.

Boundaries are lower dimensional than interiors. Disjunctions are easier to satisfy than conjunctions. Falsification is more decisive than confirmation.

The walls are always easier to find than the center.

Here’s something interesting, you can directly cause the avoidance of something in your life. For example, don’t text your ex at 2am. Don’t invest money you can’t lose or don’t take the job that makes you miserable. You get it.

These are fully within your control, you simply don’t do the thing.

Now, the asymmetry. You cannot directly cause positive outcomes. You can’t cause love, you can Only create conditions. You can’t cause creative breakthroughs. Only remove obstacles. You can’t cause meaning. Only clear away what blocks it.

The positive outcomes are downstream of factors you don’t really control. While negative outcomes can be blocked by direct action.

Your sphere of reliable agency is mostly negative.

Ancient wisdom understood this.

If you look at the Ten Commandments, eight of ten are prohibitions. Thou shalt not. Don’t murder. Don’t steal. Don’t lie. Don’t covet.

It’s succinct. Enumerable. There’s walls you can locate.

The positive commandments such honor your parents or Keep the Sabbath are vague enough to require millennia of interpretation.

And every major ethical system converges on the negatives. Don’t kill. Don’t steal. Don’t betray. The prohibitions are generally universal across cultures and centuries.

Where the positive prescriptions diverge wildly. Pursue virtue, maximize utility, follow duty.

Convergent on the negative and divergent on the positive.

You can command “do not kill.” You cannot command “be good.”

Why? Because the negative is where agency lives.

So what do we do with this?

If reality is asymmetrical and if the positive is harder to find, harder to specify, harder to cause, how do we live?

We live like sculptors.

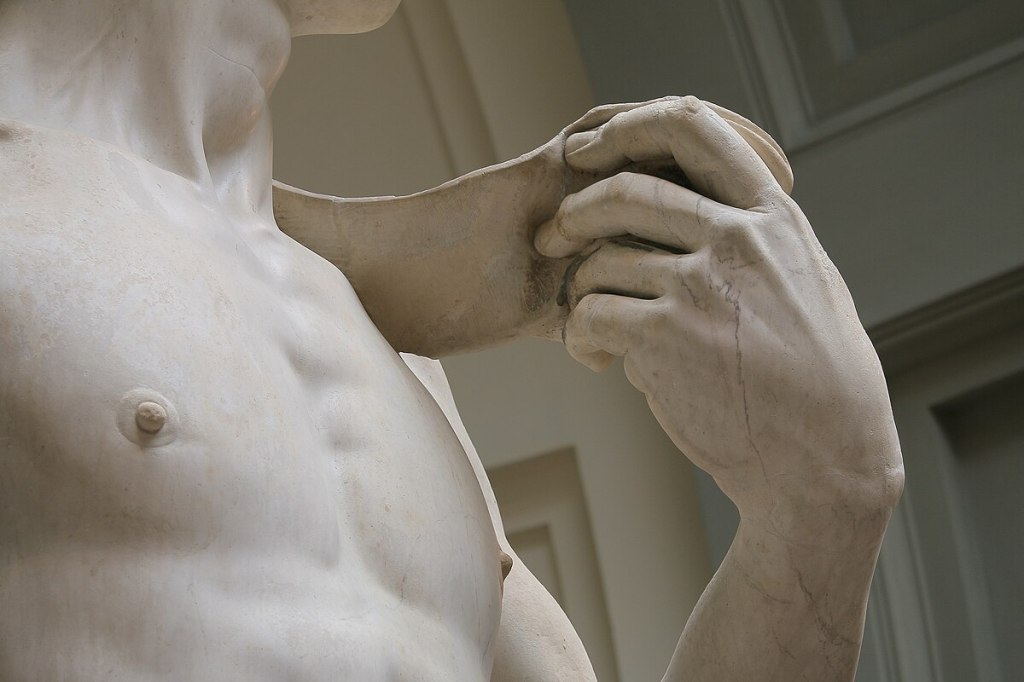

Michelangelo supposedly said he just removed everything that wasn’t David.3 The line is probably not a direct quote, but it works because it’s structurally true.

The sculptor doesn’t build the statue. He removes what isn’t the statue. The David was always in the marble and the work is subtraction.

This does not mean the positive is fake. David is real. The good life is real and so is meaning.

It means the path to the positive runs through the negative.

You don’t construct the life you want, but you chisel away the parts that definitely aren’t it.

1 I’m simplifying here, but the basic idea is wild… your immune system doesn’t have a list of every possible threat. It can’t, new viruses mutate constantly. So instead it learns what you look like and attacks anything that doesn’t match. The technical term is “self/non self discrimination.” Health is basically your body successfully rejecting everything that isn’t you.

2 See Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, First Part, Question 3. Aquinas writes: “We cannot know what God is, but only what He is not.” The via negativa (apophatic theology) appears across traditions. See Maimonides, Pseudo-Dionysius, and Eastern Orthodox theology. The pattern here is that some realities can only be approached by negation.

3 The quote is commonly attributed to Michelangelo but has no verified primary source. What we do have is Giorgio Vasari’s account in Lives of the Artists (1550), where Michelangelo describes sculpture as “liberating” the figure already present in the stone. The false version is honed, but the underlying idea is genuinely his.